16 January 2023

Estimated reading time: 06 minutes

16 January 2023

The recent attack on Brazil’s democratic institutions by supporters of former President Jair Bolsonaro was a powerful reminder that democracy cannot be taken for granted – as if the world needed another one. Democracies die, as the title of a landmark book of 2018 pointed out, and therefore needs to be defended against internal and external attacks.

But the defence of democracy seldom requires dramatic gestures or heroic resistance. It comes more often through the subtle, on-going tinkering of hard and soft measures. Even in the direst cases, such as the 06 January 2020 attack on the U.S. Capitol, lawmakers chose not to respond by the outright expulsion of then President Donald J. Trump or the mass arrest of demonstrators. The chosen antidote was a careful, smart and firmly demonstrated respect for the proper functioning of the democratic institutions themselves – and a determined effort to balance the country’s rule of law needs with the equally important requirement that citizens be able to express views freely.

The European Commission has taken the issue as seriously as it deserves through the European Democracy Action Plan and the proposed Regulation on the Transparency and Targeting of Political Advertising. These are necessary interventions, and bold: the first time the European Commission ventures into a previously national issue. Accordingly, the proposed regulation takes a careful approach, expanding the provisions of the Code of Practice on Disinformation to capture the full value chain of disinformation campaigns, such as advertising agencies and consultancies. Rather than trying to create an “arbiter of truth,” the proposed regulation wisely limits the intervention to two instruments: harmonising transparency requirements for political advertising and forbidding amplification and targeting based on sensitive data.

Yet the debate that has broken out surrounding the proposal – and the proposed amendments to it – have exposed a dangerous trend that could have devastating consequences to the measure’s overall effectiveness – and to democracy itself. Put simply, some decision makers – including powerful European Union member states – have pushed to radically extend the definition of the scope of political advertising, which will have very negative consequences on democracy if it succeeds.

To be sure, regulating political advertising is a delicate task. Contrary to what might be expected, political advertising is less strictly regulated than commercial advertising. Politicians are held less accountable for what they say than commercial corporations because “political advertising is the highest protected form of speech” as three political scientists pointed out in a recent analysis. The balancing act that arises from this privileged place – a balance between the system’s needs to respond robustly to moves to destroy it and the opposition’s right to express itself forthrightly – is the very DNA of liberal democracy. As former Italian President – and antifascist resistance leader – Sandro Pertini put it, “I say to my opponent: I fight your idea which is contrary to mine, but I am ready to fight at the price of my life so that you can always express your idea freely.” This principle is more important than ever at a time when governments worldwide are increasingly restricting the freedom of the Internet by limiting access, content and user rights as the 2022 edition of the Freedom on the Net report vividly demonstrates.

In the European Commission proposal, the regulation defines political advertising not only as ads by political actors, but also as ads on societal and controversial issues “liable to influence” a regulatory process or voting behaviour. The most recent position adopted by the Council of the European Union – the EU body representing the 27 member states – further extends this to include non-paid ads by stating that safeguards should be introduced “regardless of whether the political advertising involves a service or not.” If adopted, this position would extend the transparency requirements and targeting limitations to a much wider set of cases beyond advertising, including social media campaign on political topics. One recent analysis – by three leading University of Amsterdam legal scholars – says the measure if approved this way could potentially reach all political speech in general.

There is no doubt that amplification and targeting of political advertising is a risk for democracy. We all cringed when discovering the outrageous practices of Cambridge Analytica, which was caught illegally gathering data through a rapacious, misleading app and trying to use that data to target voters in campaigns without the knowledge or consent of the data generators in the first place. But fighting such practices should not result in disproportionate provisions that could ultimately stifle the crucial right of civil society to democratic mobilisation. Put simply, it should not subject unpaid political campaigns to the same rules and constraints as paid political advertising. These new proposals do not withstand a risk-based analysis on the cost and benefits of the intervention; they focus disproportionately on the dangers rather the benefits of data-driven campaigning.

Facts paint a nuanced picture. The official investigation of the Cambridge Analytica affair led by the United Kingdom’s Information Commissioner’s Office clearly states that the actions of the now defunct UK-based data analysis company had limited actual impact on democratic elections, that the company was “not involved in the EU referendum campaign in the UK” and that most of the methods used weren’t some sort of innovative trick but “well recognised processes using commonly available technology.” In summary, this was more a story of one company breaking the law and overselling its services than successful voter manipulation. Yet, this case takes a pivotal role in the impact assessment of the proposed regulation, being mentioned in the very first page and nine more times in the text.

On the other hand, the current debate overlooks the very real positive impact that many digital campaigns by civil society have on the policy debate and, paradoxically, on defending democracy. As professor Nina Hail shows in her new book Transnational Advocacy in the Digital Era: Think Global, Act Local, online advocacy organisations have been able to mobilise millions of users on thousands of causes, including the fight against populist leaders, through well targeted (and virally amplified) online campaigns. For instance, MoveOn in the U.S. and Skiftet in Sweden managed to exert public pressure on business leaders not to take part in the business advisory council launched by President Trump, ultimately leading to the collapse of the councils. In Hungary, online campaigning platform aHang has taken a leading role in limiting the power of Prime Minister Viktor Orban, for instance forcing the government to back down on its proposal to reform home care for disability.

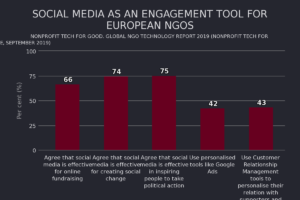

Beyond these individual stories, digital campaigning is a crucial instrument for civil society. In the most recent Global NGO Technology Report, the vast majority of European NGOs agreed that social media is effective for creating social change (74%) and in inspiring people to take political action (75%). 42% use personalised tools like Google Ads. 43% use Customer Relationship Management tools to manage their relation with supporters and donors. A more recent survey of U.S. non-profits found that 60% of NGOs invest in paid advertising. Making it more difficult to use these tools will affect mostly those organisations, like NGOs, which have been able to overcome resource limitations against larger established players by making smart use of technology and taking advantage of recommendation algorithms to “go viral.”

There is no doubt that political advertising presents a regulatory gap and that transparency and targeting are some of the most important areas of intervention. But effective regulation wisely weighs the costs and the benefits of an intervention, in particular when it comes to fundamental rights such as free speech. Placing political speech in the same regulatory bucket as political advertising will weaken, rather than reinforce, our democracy.

David Osimo is director of research at the Lisbon Council.