18 January 2021

Estimated reading time: 06 minutes

18 January 2021

Platforms have come under great scrutiny in recent years, and it isn’t hard to see why. The disruptive peer-to-peer interaction they pioneered has created new global markets for goods that once struggled to find buyers locally, ushered in a new standard of on-demand shopping choice (including to-your-door delivery) and opened up pathways for deeper connection, creation and direct communication.

It’s particularly amazing when you remember this: not so long ago the world’s largest companies were little more than unruly bands of California-based misfits with hippy-like ideas about how businesses could be operated and workplace culture run. No más. Today, the five largest among them – Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Microsoft – boast a market capitalisation above €5 trillion, more than the entire Euronext, Europe’s largest stock exchange. The company founders no longer report regularly to the office; they’re busy spending their fortunes on global philanthropy where their work to fight disease and eradicate famine has become as important as many international agencies’ and governments’.

Along with success has come greater scrutiny, but are the charges leveled at these insanely successful companies always fair? The European Commission, for one, has invested enormous capital in a new concept: the idea that many U.S.-based platforms have become “gatekeeper” companies that use their size to squeeze rivals, entrench commercial positions, deny consumers choice and stifle innovation. According to the proposed digital markets act – and its sister, the digital services act – companies that grow above a certain size should be subject to a special list of “do’s and don’ts” that would not apply to younger, smaller companies. These include forced access to commercial data for third-party vendors, new rules allowing consumers to delete core apps and special rights for third parties to sell their rival services on the platforms themselves. Companies that meet the “gatekeeper” criteria and refuse to submit to the enhanced regime face a dreary fate: forced sale of assets, the lifting of some intellectual property protection and fines that could reach 10% of global revenue.

But what exactly is a “gatekeeper?” The proposed regulation sets a relatively high bar: 1) €6.5 billion of turnover in the last three years, a market capitalisation of €65 billion in the most recent financial year and cross border sales in three or more European Union member states; 2) 45 million monthly active users in the EU and 10,000 or more active business users in a single year, and 3) a market position that appears “entrenched.” The fact of having reached these thresholds, the European Commission says, could grant large companies “the power to act as private rule-makers and to function as bottlenecks between businesses and consumers.”

Does the evidence support the charges? For starters, there is much to show that, far from perceiving the large digital platforms as “gatekeepers,” many small businesses see these unique cross-border vehicles as “market makers,” whose giant consumer base and easy-to-use displays offer crucial pathways to consumers and create opportunities they might otherwise have missed. The pattern of advertising on Facebook, for one, is telling; more than 75% of Facebook’s advertising revenue comes from small- and medium-sized businesses – a sign that many SMEs are highly active here and see this 2.5 billion member platform as a good place to find new business and at a very low cost. A Facebook ad can reach a carefully curated audience of several thousand potentially interested people for as little as €200.

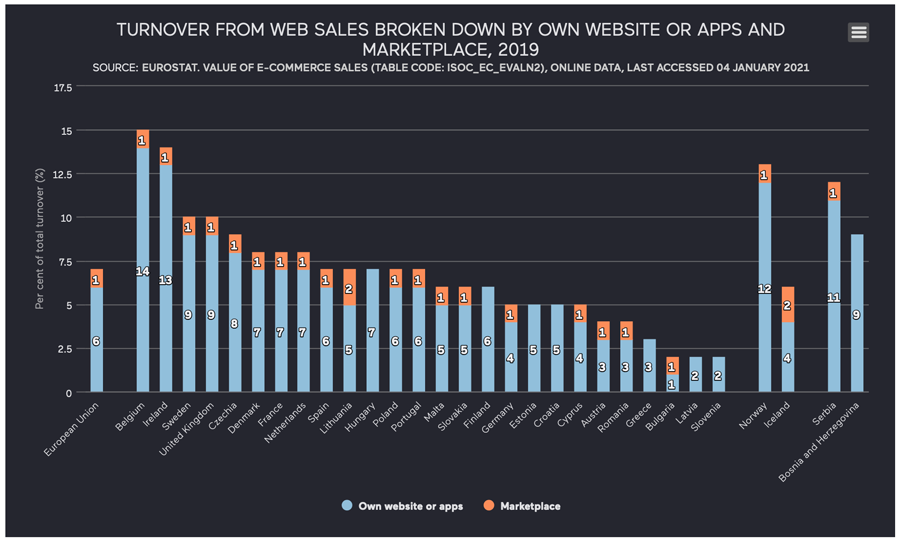

The economies are great, for sure, especially if you’re a small company and new customers are a crucial determinant of your success. But has it led to unfair outcomes? Here, again, the evidence would show that it has not. Indeed, there is very little evidence of any “gatekeeper” effect in the real world itself, even as the platforms themselves become a more common part of daily life and the word “gatekeeper” is bandied about as if its existence were self-evident and requiring of little proof. Despite decades of discussion and active encouragement, online commerce today amounts to barely 7% of EU companies’ sales, according to Eurostat.

And while that share has been expanding, most companies still report vastly more sales over their own websites than through platforms.

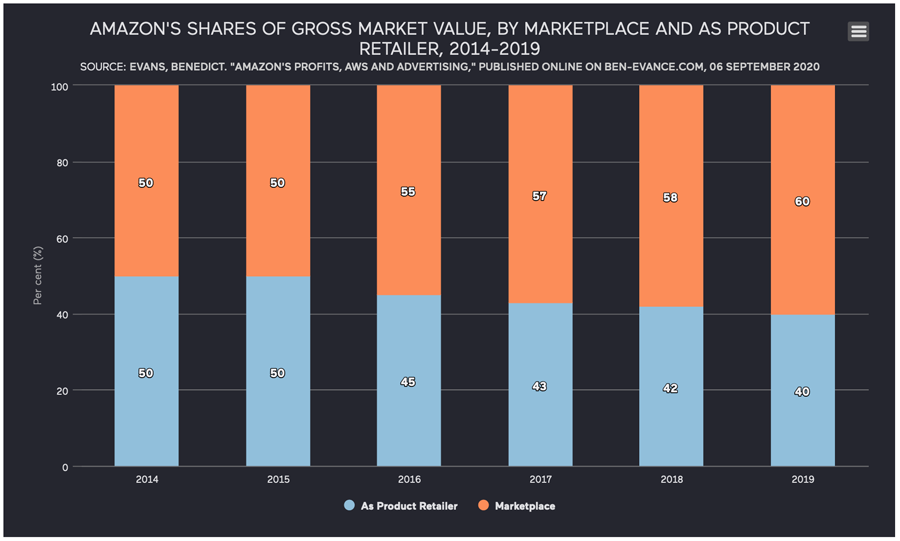

Amazon.com figures tell a similar story. In a separate competition case, the European Commission has accused Amazon of using its data to drive rivals out of business; this is not the place to judge the evidence and the Lisbon Council has a policy of not commenting on individual competition cases (though we are happy to talk about competition in general as a policy matter). But it might be worth noting that, according to calculations from Benedict Evans, a technology analyst who tracks Amazon’s market performance, more than 60% of Amazon’s revenue still comes from market-place fulfilment for third-party vendors. It is hard to imagine that Amazon would aggressively go after a key part of its core business to sell – what? – Amazon-branded soap?

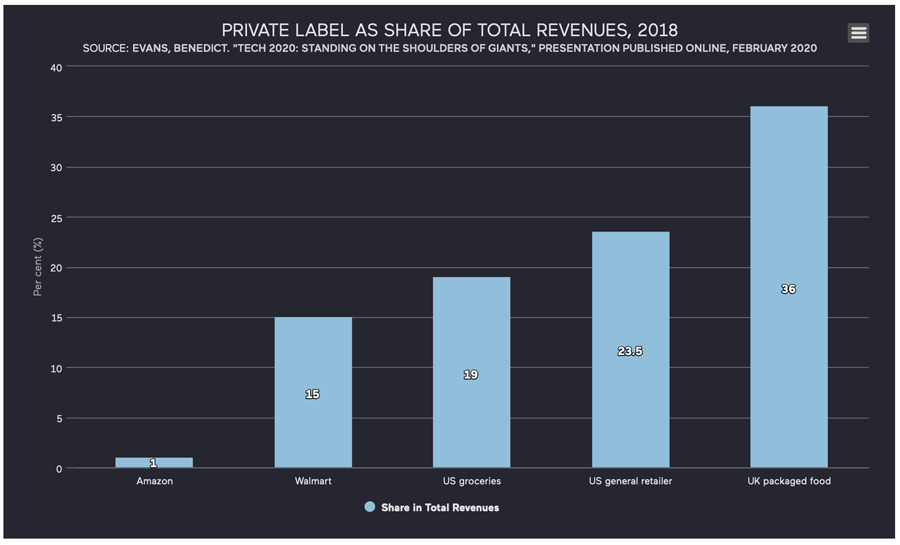

By the way, Amazon’s self-branded goods – a common way of moving low-cost generics in high-volume operations – is still a fraction of the similar business done at mass-market stores like Walmart and United Kingdom packaged food vendors.

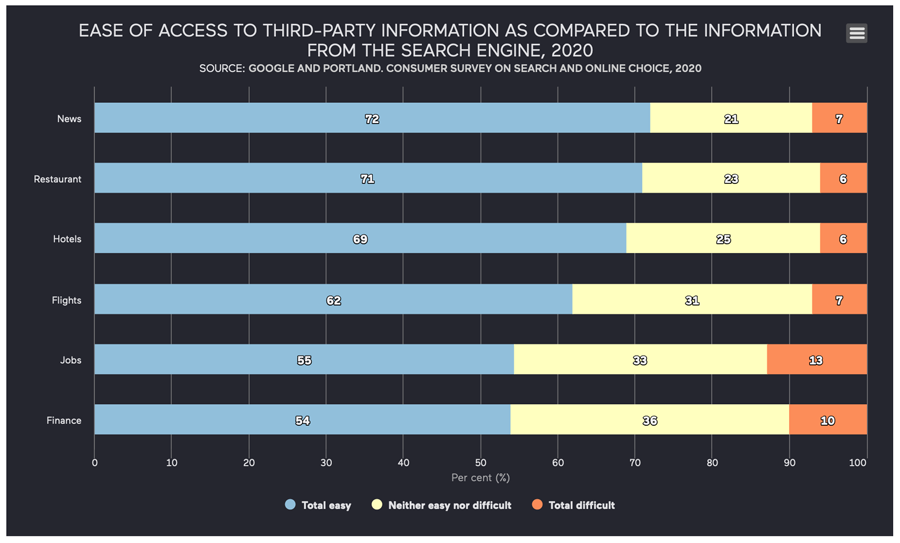

The European Commission makes similar charges against Google, and has argued in a series of big-ticket cases that Google uses its search engine to promote its own products and prioritise information favourable to Google products. A recent consumer survey from Portland, the UK-based market research institute, showed that more than half of Google’s users reported no difficulty accessing third-party information on the hugely popular search engine; complaints that objective information was hidden or hard to find on Google came from fewer than 10% of respondents.

Europeans have every right to be worried about their relatively weak position in the digital age. Of the world’s 15 most successful technology companies, all are American or Chinese. In the top 200, only eight are European. This has led to much talk about how Europe – the heart of the first, second and third industrial revolutions – could be so definitively shut out of the fourth.

But much of the explanation for this relatively dismal performance lies in the attitudes on display in these efforts to legislate. Rather than developing a comprehensive strategy for building up global digital champions and creating the conditions for European company growth – something which the previous European Commission, led by President Jean-Claude Juncker, embraced and aggressively championed – the new European Commission prefers to go after successful companies with regulation and inspire European conglomerates with protection and patronage, as if aggressive use of state power alone will somehow translate into European commercial success. Today, the Germans and their European patrons promote “Europe-first” policies in the digital field, like the Gaia-X “federated data infrastructure for Europe,” as if a “made in Europe” label on a digital product will be enough to see queues forming up on the streets on launch day. Others want to put protectionist restrictions on the processing, storage and analysis of “European” data in Europe.

The problem is that the recent legislation only punishes global companies not for what they do but for who they are. It imposes an artificial ceiling on success, applying special rules to slow down the winners and implying that success at a certain level is something to be avoided at all costs. Even worse, it grants the crucial decision – who is a “gatekeeper” and therefore subject to special rules? – to a team of unelected European bureaucrats working from a not fully transparent crib sheet and with an avowed mission to restore Europe’s “digital sovereignty” at whatever cost. Call it what you might, but this is not tough competition policy; this is “pre-crime” of the sort Tom Cruise fought so valiantly in Minority Report, the 2002 film.

The fact is, most of the “American” platforms grew to be large the hard way; they conceived of and delivered good services to consumers at very low cost and they understood the value and role of “scaling up” in bigger markets as a way of ensuring survival and guaranteeing success. Shopify Inc is a case in point. This Ottawa-based startup sells off-the-shelf interfaces and back-office applications to customers wishing to set up their own online commerce store. And where does much of that commerce take place? On Amazon, where Shopify is a major sub-component of the flourishing community of entrepreneurs who make very good livings on this gigantic global platform. Far from shutting out a potential rival, Amazon curtailed its own Amazon Webstore service and now works with Shopify-powered SMEs to grow a bigger market. And these days Shopify’s activities extend well beyond Amazon’s border; it even competes directly with Amazon on product fulfilment, a major line of business for both companies. By the way, the founder of Shopify, Tobias Lütke, is German. He lives in Canada, where he found the partners, mentors and venture capital needed to develop this innovative new service.

There might indeed be areas where platforms can and should be more closely regulated; but commerce is not necessarily one of them. To the contrary, digital platforms have, arguably, done more than national governments and European civil servants to deliver a truly “single market” for European goods. That success should be celebrated and built on – not capped with artificial ceilings or “black-list” based legislation. Ceilings and thresholds are a formula for stopping economic activity at a certain level and punishing winners with arbitrary rules. They actually disincentivise the growth they are intended to facilitate. Europe and European entrepreneurs need a growth strategy worthy of the name.

Paul Hofheinz is president and co-founder of the Lisbon Council.

Download in PDF