09 October 2024

Estimated reading time: 06 minutes

09 October 2024

John Maynard Keynes, the English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of the economic policies of governments, once said: “The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.”

This is particularly true and it will be the biggest challenge for the new executive vice-president for tech sovereignty, security and democracy, Henna Virkkunen. The outgoing commissioner, Thierry Breton, leaves behind a messy policy vision about Europe’s digital infrastructure future, mainly biased towards an old and conservative thinking about innovation and investment, often leaning towards protectionism. The new European Commission should avoid this trap. The Internet is and should remain a powerful piste for collaboration, communication, information exchange, research and entertainment. Efforts to bundle business models as diverse as online services and infrastructure – and to regulate them with rules clearly intended to favour one part of the ecosystem over another – are doomed to fail.

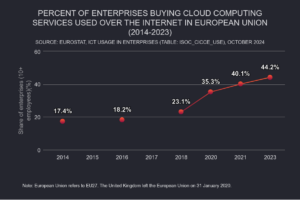

The most recent battle in this war is taking place over recent efforts to bring all Internet services – including cloud computing – under a single regulatory umbrella where Europe’s giant telcos would dominate and could dictate terms. Cloud, for sure, is one area where adoption is rising quickly. In Europe alone, cloud was being used in 44,2% of companies by 2023, roughly in line with the ambitious 75% target set out in Europe’s Digital Decade: Digital Targets for 2030, the goals Mr Breton set in a 2021 communiqué.

And yet, the European Commission warns in its recent white paper that the current regulatory framework for cloud – a uniquely open system in which unbiased network access is guaranteed and portability of data is legally mandated – is not fit for purpose. The problem – implied, but never quite stated – is that Europe’s cloud services are not very popular. Many see them as overpriced compared to equivalent offerings (one famous incident involving a European provider ended in actual service failure, data loss and law suits. Instead, to correct this hypothetical “market failure,” the European Commission proposes that the European electronic communications code, the framework that regulates telecom networks and services, should be expanded to cover cloud providers as well.

According to advocates of the move, this would generate a “level-playing field” in which Europe could compete better. But to others, it would merely provide the opportunity to weave European champion-boosting provisions into the code, absolving European digital service providers of the need to compete on a truly level playing field and doing untold damage to the smooth functioning (and overall consumer experience) on the Internet as well.

Policy wouldn’t be policy if an initiative like this didn’t create an avalanche of comments, reports and roundtables – and the Lisbon Council is no exception. In September 2024, the Lisbon Council brought together a host of experts from different fields – telecom operators, cloud providers, economists, academics and civil society representatives – for the High-Level Roundtable on Digital Infrastructure and Regulation: What Next?. The majority of participants argued that any change to the current status should be subject to evidence and a clear impact assessment exercise, where consumers are at the center. As was repeatedly stated, given the lack of actual market failures, it is hard to justify any regulatory intervention.

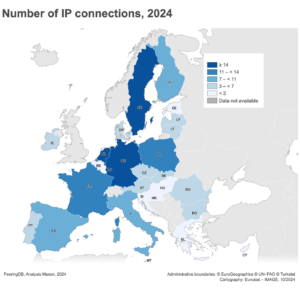

A report – The European Telecoms Regulatory Framework: Not a Good Fit for the Public Cloud – was launched at the High-Level Roundtable. Commissioned by Amazon Web Services and produced by the non-partisan consultancy firm Analysys Mason, it dove deep on the importance of the so-called “IP Interconnection market,” the complex network that physically links one operator’s Internet Protocol network with the IP equipment and facilities that belong to another network, thereby allowing seamless exchange of data and preventing any one network from abusing its dominant position in a local setting., As is, Europe is home to 167 peering locations according to the study, demonstrating “the wide distribution of interconnections points used by cloud providers and IT networks.”

The Analysys Mason paper continues, “as [the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications or BEREC] states very clearly in its recent consultation paper on this topic, IP interconnection on the Internet has worked and continues to work very well in the absence of regulation.” Perhaps this is why a strong majority of respondents to a European Commission consultation – some 67% – said they oppose regulatory intervention in the interconnection market, according to Unlocking the Future of Connectivity: An In-Depth Analysis of the Public Consultation on the White Paper, a new paper from Political Intelligence, a Brussels-based consultancy.

Because of the Internet Protocol, access, content and service providers are connected to each other with the purpose of serving end users. This market, therefore, is extremely important for the delivery of online access: if something goes wrong, there will be implications affecting user experience; services will falter, function slowly or not at all.

Usually, IP interconnection takes two forms: peering, i.e. direct information exchanges between the parties; and, transit, where a third party is responsible for the delivery of content. The majority of networks engage in peering agreements, because they are more efficient, and they serve end users better. Unlike in the case of telecommunication networks and termination monopolies, the benefit of IP interconnection is that it does not require any regulation to ensure that barriers to entry remain low; the only requirement is that of collaboration, which happens seamlessly and without any bureaucratic intervention.

For the complaining from some telecommunication providers that the IP interconnection market does not provide “a level playing field,” the fact is that some of those providers seem to favour a playing field whose tilt is perceptible to any and all. The most recent example involves Deutsche Telekom AG, one of Europe’s largest telecom operators and Germany’s national telco champion. After a legal standoff, Deutsche Telekom decided not to peer directly with Meta Platforms, Inc and its services, forcing Meta to use a third-party transit provider to connect to Deutsche Telekom’s networks. This follows Meta’s decision not to pay the sizeable fees Deutsche Telekom demanded for direct peering, risking the quality of services for millions of German citizens. Barbara van Schewick, professor of law and electrical engineering at Stanford, has captured the outcome – an online flood of complaints about deteriorated services on Deutsche Telekom.

In A Deutsche Telekom Shakedown: Will Instagram, Facebook and WhatsApp Slow to a Crawl in Germany as Deutsche Telekom Tries to Get Paid Twice and Will German Regulators have the Courage to Stop Deutsche Telekom’s Bullying, she describes the outcome of the dispute this way: “If you buy internet access from Deutsche Telekom, you pay Deutsche Telekom for a fast connection to the internet. But whether the apps and services you want to use actually work well, completely depends on whether they have paid Deutsche Telekom’s ransom.” The striking thing about this case though is that the trouble arises because Deutsche Telekom already does exactly what it has been lobbying the European Commission for the past five years to do to the entire sector: charge network fees.

If the past five years taught the European Commission anything, it is that the vision telecommunication providers have for shaping Europe digital market does not have wide support as the Fair Share Repository documents. The problem with Commissioner Breton’s vision was that, in order to reform telcos, he was convinced he had to bring down the entire internet. And this has always been the telcos’ problem. They never liked what the Internet did to them.

If the European Commission wants to discuss telco reform, they should be doing things like encouraging the harmonization of the implementation of the European electronic communications code across Europe to avoid the patchwork of different regulatory transpositions from one member state to the other, which dilutes the progress towards a single market in Europe. The ongoing evolutions in the market and in technology present great opportunities, for example to offer communications services across borders while not having to worry about deploying infrastructure because it can be leased from other, neutral actors; or the ability to focus know-how on what certain companies are better at, either service or network management. This, in turn, can benefit both company profitability through economies of scale and consumer choice through a more diversified range of offers.

Under the leadership of Henna Virkkunen, the European Commission has the opportunity to focus on a more positive agenda, fostering sustainable economic, environmental and social benefits across Europe through digital transformation.

“To master Europe’s digital infrastructure needs,” as the white paper cited at the start of this Forum intervention proposes, there are a number of positive avenues to consider. We can do so by focusing public policy efforts on enabling a digital society, including a broad competitive ecosystem of connectivity, investment, content creation and infrastructure, provided by a range of players.

There is a new set of brains that will be leading the European Commission’s agenda and they hopefully will come with new and fresh ideas of how to approach the discussion about digital infrastructure in Europe. For the past five years, the European Commission’s vision on enhancing digital infrastructure has been myopic and borderline dangerous. It’s time to move on.

Konstantinos Komaitis is senior researcher and non-resident fellow at the Lisbon Council and senior resident fellow at the democracy and tech Initiative at the Atlantic Council. For 10 years, he served as senior director the Internet Society, a global non-profit.

Download in PDF