In these days of crisis and lockdown, digital government has suddenly become an essential service.

07 October 2020

Estimated reading time: 04 minutes

07 October 2020

Having endured four days and four nights of acrimonious debate, supporters of the European ideal drew a collective sigh of relief in the early morning of 21 July 2020, when the continent’s 27 heads of state and government emerged from the European Council marathon with agreement on Next Generation EU (NGEU), as well as a multi-year European Union budget through 2027.

As is in the nature of compromises, there were a number of aspects that observers lamented: the breakdown between grants and loans, the cuts to important EU-wide programs, the weasel wording on the respect of the EU’s rule of law and more. But such reservations were eclipsed by the awareness that the agreement embodied one, significant innovation: the authorisation given to the European Commission to tap the capital markets, on behalf of the EU, for €750 billion to fund the Next Generation EU – the largest ever euro-denominated issuance at supranational level.

For the first time in its history, the EU is to be allowed to borrow to finance expenditures as a collective body, overcoming two historic taboos standing in the way of European integration: first, a staunch opposition to EU common issuance and, second, an equally persistent resistance to explicit fiscal transfers across countries. In contrast, the initiative implies a degree of fiscal burden sharing, and could constitute an embryo of the missing link in Economic and Monetary Union: a centralized fiscal capacity, as noted also by the European Central Bank.

Many observers have drawn an analogy between the NGEU agreement and a watershed in U.S. federalism, defining it a “Hamiltonian moment” – with reference to 1790, when Alexander Hamilton pressed that the federal government assume the states’ war debts. European Council President Charles Michel drew another historical analogy, dubbing the agreement a “Copernican moment.” And the Financial Times saw echoes of Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon.

The agreement certainly crosses long-standing red lines, and can thus be viewed as a breakthrough in European integration. Does it however rise to the above level of hype? Not quite, or at least not yet. First of all, almost three months after the European Council conclusions, the agreement is still in abeyance, awaiting European Parliament consent and member states’ ratification. The first will be forthcoming, especially after the “political agreement” reached by the council of ministers on 06 October on the RRF’s workings. For its part, however, national ratification hangs in the balance (notably in Hungary and Poland), threatened by the vexed question of the rule of law.

Assuming these obstacles are overcome and the agreement enters into effect, there remain two operational issues that will shape the ultimate judgment on the initiative:

First, how smoothly will the disbursement approvals proceed? Governance of the disbursements was a highly contested issue at the July European Council. The European Commission’s initial proposal was for a slim process with a central role for itself. The so-called “frugal” countries (Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden), in contrast, pushed for political veto power. This would have been highly deleterious, making for a purely intergovernmental governance structure, with the related prevalence of narrow national interests and the prospect of ill-tempered all-night disputes. As I have argued elsewhere, that would have constituted a “diabolical persistence” in error of the 2010 euro area crisis. It would have been clearly antithetical to the rationale of a mutually shared recovery from the common economic shock of a pandemic.

Fortunately the extreme solution of one-country veto power was averted. The final compromise envisages a somewhat convoluted “emergency brake” in case of disagreements, which could slow down disbursements for up to three months “as a rule,” with however the European Commission’s assessment likely prevailing in the end. There are however risks that events will not unfold quite as smoothly as that, and there is a potential for renewed European tensions with negative consequences, including on the recovery itself.

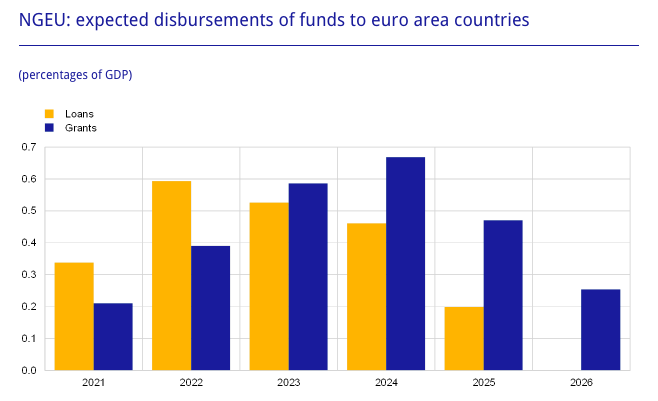

Even assuming smooth decision-making, the NGEU’s success will depend on a second factor, the quality of the spending it finances. Given the timeline of disbursements (mainly in 2023-24 – see chart below), the funds will no longer be able to play a countercyclical role. Their objective must therefore be that of boosting Europe’s long-term growth potential via high-quality projects.

How to secure quality spending throughout all member states? As argued in Why the Quality of Public Finance Matters, the focus of European surveillance needs to shift away from its single-minded fixation on fiscal deficits. Deficits are the result of the tiny difference between two much larger quantities, total revenues and total expenditures – both around 50% of gross domestic product in most member countries. The ongoing reviews of the fiscal rules and related surveillance procedures need to ensure much greater attention to the quality of these two large aggregates, thereby delivering a true qualitative change.

In sum, for the reasons noted, the NGEU does stand to be a true watershed. To this end, we have to assume (bravely) that the plan is not undermined by divisive decision-making on country-specific disbursements, poisoning the well. And that its effectiveness and credibility are not undermined by wasteful spending. Assuming that these two conditions are fulfilled, then the July agreement would indeed constitute an important turning point, marking 2020 as a milestone in European integration.

It is however a brave assumption, and there is likely many a slip ‘twixt that cup and lip. In truth, despite the progress, testing times still lie ahead for the EU and it would appear safer, for now, to take a step back and forgo high-sounding invocations of Hamilton, Copernicus and even the Rubicon.

Alessandro Leipold is chief economist of the Lisbon Council. Previously, he served as acting director of the International Monetary Fund’s European Department and later as IMF executive director for Italy, Albania, Greece, Malta, Portugal and San Marino.

Download PDF