16 July 2021

Estimated reading time: 06 minutes

16 July 2021

The €672.5 billion recovery and resilience facility – agreed with much fanfare in July 2020 – is now fully operational. The approval in July 2021 of the first batch of national recovery and resilience plans by European Union economic and finance ministers allowed cash to begin flowing. As of July 2021, 12 EU countries stand to receive “pre-financing” disbursements of up to 13% of the country’s allotted support.

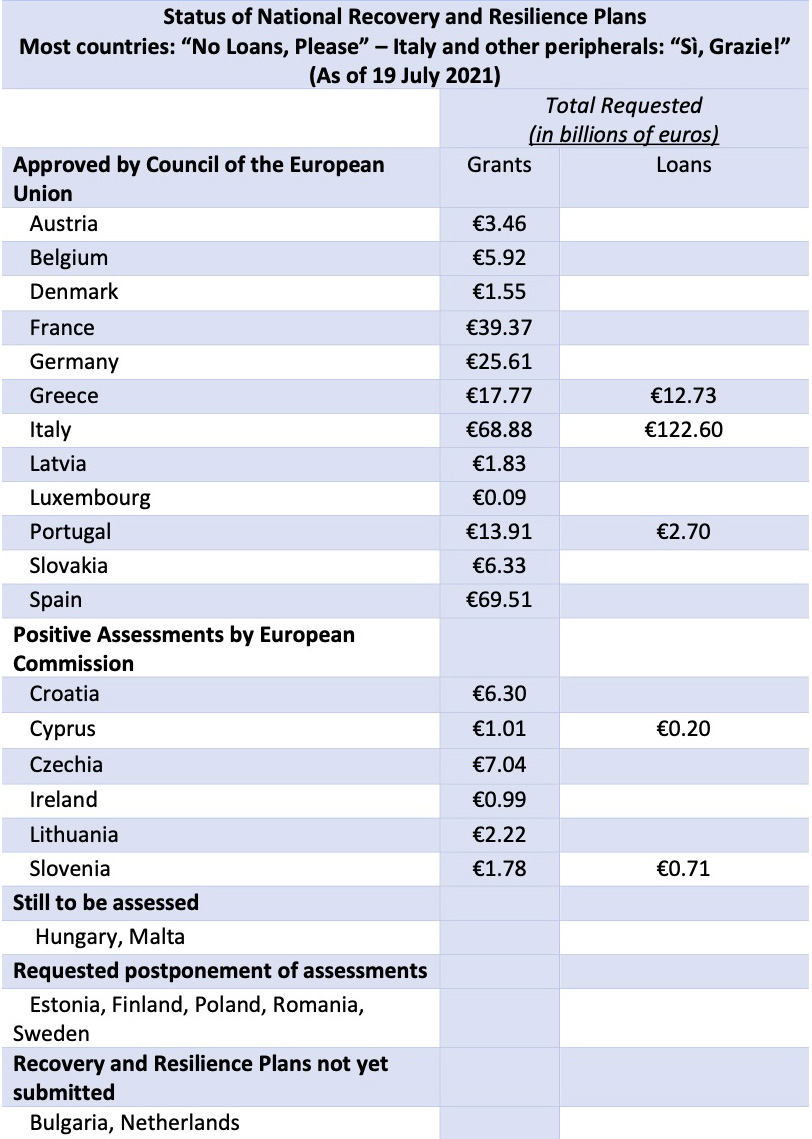

Sources: The European Commission and Lisbon Council calculations

With the payouts started, it is perhaps time to assess how the facility has fared in its early stages and what that performance tells us about future European Union economic developments. To date, two major trends are clearly visible: 1) despite the facility’s difficult birth, European Union member states like the programme and are cooperating with an unusual degree of comity to make it a success; and 2) countries may not have understood what they wanted or needed when they spent four long days and nights sparring across the surreal platform of a 27-head-of-state Zoom call. Several countries – including Austria and Denmark – opposed heavy reliance on grants in the package, but in the end grants are what they asked for and grants are what they got. Others – like Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia – had opposed loans and the attached conditionality – but in the end they went for loans as well and will receive both loans and grants.

The mixed signals and sometimes unexpected requests are not the central point. The biggest lesson is the model is working. And it could well prove a blueprint for future emergency-funding mechanisms and for more effective EU economic governance.

But to get there a smooth launch was crucial. This was important not only because of the programme’s size (it accounts for 90% of the €750 billion flagship New Generation EU programme), but also because of the much-heralded innovation on which it was based: common borrowings with an implied degree of fiscal burden sharing. This unprecedented step inspired analogies with a watershed event in United States federalism – the “Hamilton Moment” when, in 1790, 13 U.S. states agreed jointly to assume the young country’s war debts based on the advice of Alexander Hamilton, the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

So far, the European process has moved forward relatively easily. Some important shoals on which the programme could easily have foundered have been dodged without difficulty. Despite the rancour and divisions at the four-days-and-four-nights summit, ratification in national parliaments was – apart from some local drama – uncharacteristically conflict-free and on schedule. That harmony opened the way to the first tranche of European Commission-led borrowing in mid-June 2021, which was hugely successful, with demand more than seven times higher than the €20 billion of bonds on offer. Going forward, street wags see more easy sailing for European Commission issuance with borrowing volumes set to average about €150 billion a year through 2026.

Meanwhile, the national recovery and resilience plans submitted by EU member states have been subsequently endorsed by the European Commission at a steady clip, beginning with Greece, Portugal and Spain in June 2021. As of 19 July 2021, 18 plans had been approved by the European Commission. Admittedly, the modus operandi seems to be on grading lightly so the whole class will pass uniformly. All 18 plans assessed to date received the same grades: an A on ten of the eleven criteria examined, and a B on the remaining one (the method used to assess costs). This of course reflects an obvious aversion to any form of “naming and shaming” in a moment of crisis, but it strains credulity that all national plans were uniformly of the same quality and had only one minor shortfall in the same area.

That said, it is significant and highly welcome that the initial disbursements have gone smoothly – the governance of disbursements having been one of the programme’s hotly contested issues. The argument between those advocating a strong role for the European Commission and others who favoured a national veto (a process which, if approved, would have been disastrous) was resolved with a somewhat convoluted compromise, dubbed an “emergency brake,” which envisages a three-month delay in disbursements and consideration by the European Council in case of disagreements. In practice, there has been no political appetite to criticise the national plans once endorsed by the European Commission, and the European Council has approved all 12 decisions placed on its table. In the absence of disagreements, the “emergency brake” – a recipe for confrontation, acrimony and tension – has not been touched.

As to the recovery and resilience facility’s impact, the amounts effectively made available are set to fall short of the €672.5 billion allocated for an interesting and perhaps predictable reason: the widespread reluctance to request loans (with the accompanying conditionality) under the facility. Notably, the countries that fought hardest against outright grants and pressed for an emphasis on loans (including two of the so-called “frugal four” – Austria and Denmark) have requested only grants, while the only countries that have requested loans are those who most opposed them in the negotiation (notably Cyprus, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Slovenia). The result is that part of the loan allocation of the facility (€360 billion, or 54% of the total recovery and resilience funds) will likely remain unused, reducing the facility’s total firepower and diminishing the overall EU response, which has itself already been criticised as insufficient by some observers.

While the initial process has been smooth, the more difficult tests are yet to come. Some of the more contentious cases (notably in Eastern Europe) have not yet been assessed. Furthermore, the current “pre-financing” is dependent only on endorsement of the national plans from the European Commission and approval by the Council of the European Union. In contrast, the remaining 10 tranches (running through end-2026) will be subject to monitoring of implementation and observance of specific targets and milestones. Monitoring could well become contentious, not only in countries such as Hungary and Poland, but also in the facility’s main recipient, Italy, given a prospective change in government leadership after general elections due no later than 01 June 2023. Clearly, monitoring of implementation is where the facility’s rub will lie, and the process is likely to alter EU surveillance appreciably. Already, preparation of the recovery and resilience plans has generated much greater domestic debate and ownership than the stability programmes and related country-specific recommendations under the old European semester process. This is in itself a significant step forward, as the lack of ownership for the stability programmes accounted for much of the recommendations’ non-observance. Now, furthermore, there is the added carrot of money, and EU surveillance faces a potential qualitative leap.

But the facility’s impact on the European construct more generally seems unlikely to live up to the predicted “Hamilton moment.” Common borrowings for fiscal transfers are not on their way to becoming a permanent feature of the European architecture at any time in the foreseeable future. The continued impasse on banking union and the opening salvos on new fiscal rules that will replace the rules suspended in 2020 (aka, the stability and growth pact), with traditional battle lines being again drawn, are not promising omens. That said, precedent has good standing in European affairs: once broken, a taboo is no longer such and a mechanism along the lines of the recovery and resilience facility could well be used again if the need were to arise.

As so often in Europe, there are both bright spots and clouds. Hopefully, the cool heads that have prevailed in the smooth roll-out of the recovery and resilience facility to date will set the tone also for its implementation going forward and for a sensible re-entry from the suspension of the stability and growth pact induced by the pandemic.

Alessandro Leipold is economic counsellor of the Lisbon Council. Previously, he served as acting director of the International Monetary Fund’s European Department and later as IMF executive director for Italy, Albania, Greece, Malta, Portugal and San Marino.

Download in PDF