27 February 2023

Estimated reading time: 06 minutes

27 February 2023

Thierry Breton has a vision. The European commissioner for the internal market wants to prepare European infrastructure for the surge that will come as the metaverse, generative AI, smart transportation and a quadrillion new data-driven services put heavy demands on a creaking European telco infrastructure. But is his vision the right one?

To many, the European commissioner and former Orange CEO is seeking answers in Europe’s murky, un-liberalised telco past – an approach perhaps befitting someone who led a major private interest in the sector for years and brought the sector and that company to the not quite awe-inspiring place where they are today. He sees a world where large telecommunication companies – Deutsche Telekom AG, Orange s.a. and Telefónica s.a. – control what you get to see and extract monopoly rents on the back of your viewing preferences. It’s a vision that doesn’t remotely hold up on the merits – unless you’re a hard-pressed telco struggling to make up for lost ground after years of nursing grievances while the rest of the world got on with the important task of modernisation.

Not even Europe’s toughest regulator – the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) – thinks Mr Breton’s plans are a good idea. As rumours circulated in Brussels of Mr Breton’s impending proposal, BEREC rushed out a preliminary assessment of the proposal. “BEREC has found no evidence that such mechanism is justified given the current state of the market,” it concluded, echoing a finding reached in 2016 when a similar proposal was rejected at the time.

But what exactly is the idea? It’s hard to say for the moment. Mr Breton has hidden it behind a complicated pile of Socratic questions – dubbed a “questionnaire.” He says he will read the responses before he publishes proposals in May. But the wording and overtly leading way the questions are phrased give a crystal-clear view of where he wants to go. “Some stakeholders have suggested a mandatory mechanism of direct payment from [content and application providers (CAPs) and large traffic generators (LTGs)] to contribute to finance network deployment,” it asks in Question 54. “Do you support such suggestion and if so, why? If no, why not?” But there is not one question about consumers or network neutrality or any of the other concerns that a proposal of this type would imply or invoke.

Overall, the proposal would set a data-transmission threshold and every company transmitting data above that threshold – in other words every company whose services and offerings were popular and widely sought – would pay a fee directly to the telco provider for the right to transmit that data at all. It’s a two-sided market, in other words. One where consumers and providers both pay. Or perhaps better said, one where the consumer pays more – because you can be sure that higher prices will be passed on to the consumer in one form or another. And what would remain is an insanely powerful middleman able to switch off European Internet access to any service provider who didn’t pay just as it can switch off phone service to non-paying users today.

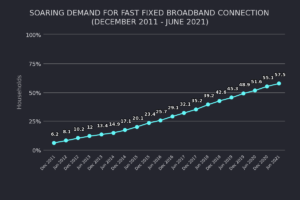

But to understand why all of this is catastrophic, you need to understand how the Internet works – and how it has developed over nearly five decades. A decentralised architecture based on open standards allowed Tim Berners Lee to envision a diverse, independent, leader-free platform for direct connection – an idea which gave birth to a wide ecosystem of content creators, service providers, data deliverers, coders, non-governmental organisations and end users. It is this immense eco-system that has driven value in the sector, and telcos – despite their grousing – have benefited immensely from it. Today, there is surging demand for broadband Internet and other services upon which European telcos profit immensely as the chart below shows. And much of that demand is driven by services – offered online but produced elsewhere.

By and large, the European Commission – and a stream of European Commissioners – have encouraged this trend, taking crucial steps to encourage new entrants and healthy competition, often at the expense of the telco monopolies that had dominated the sector for decades. The Unbundled Access to the Local Loop Regulation (2000) – an innovative proposal under which all telecommunications operators were given the right to provide services to households on an equal basis regardless of whether they own the local network – has given birth to better prices and better service to consumers – and a host of successful European entrants, such as Deutsche Glasfaser Holding GmbH in Germany or CityFibre in the United Kingdom (which left the EU in 2020). And the Open Internet Access Regulation (2015) is just as important; it enshrined the principle of net neutrality, which is the basis for free and open competition for consumer attention across the sector.

The point is, the Internet is something we built together, with many players contributing key innovations and large investments along the way. It is a not a story of one sector free-riding over the concerns and interests of another. It is a story of mass collaboration, and broad social benefit, and wide-ranging investment. It is sometimes overlooked but the U.S.-based platforms have invested massively in European communication infrastructure – not entirely altruistically, perhaps, but certainly realistically (they too want to raise the quality of Europe’s communication infrastructure). Google, for one, has invested €6.9 billion in safe data centres and undersea cables – and another €3 billion is pledged and coming. Microsoft has invested €14 billion.

And, yes, the sector does need more investment. But the way to do that is not by pitting one important part of the Internet’s ecosystem against another or igniting a populist backlash. Terms like “fair share” are loaded – precisely because there is very little that is fair about them. A raucous debate conducted around a 1980s view of technology and markets – a debate in which a wildly successful part of the Internet ecosystem is forced to subsidise a slower moving part – is hardly an invitation to the kind of dialogue Europe needs to have now. To the contrary, Mr Breton should be summoning all of the Internet players to the table. He should be a peacemaker in this process – not the instigator of conflict. He should stop using spurious arguments to raise tension or send Europe down a path where innovators are brought to heel and the slow-rolling past is subsidised at the expense of the still-to-be-born future.

And there’s another crucial point in play here as well. Commissioner Breton – and Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager – have both said the final proposal “will guard net neutrality” in a closely coordinated pair of statements released alongside of the proposal. But this argument does not stand the test. Should a content-provider not agree to an additional “distribution fee,” the only recourse the telco provider would have would be to throttle the traffic – or kick the content provider off the Internet entirely. It is disingenuous to say that a proposal of this type would not affect net neutrality. And the vehemence and confidence with which that claim is now asserted – by Europe’s two highest digital commissioners – show how well they understand that there is indeed an argument there that needs answering – even if the answer is little more than a statement of confidence in a case the facts don’t support.

All along, the Breton approach to Internet regulation has been different. Far from encouraging a thriving eco-system that keeps the Internet free and open, he has looked to defend and shore up incumbents, often putting in place policies to sustain the unsustainable and soften the pressure felt from market failure and failure to please customers. Indeed – alongside the European Green Deal, the monumental battle against COVID-19 and the tough response to illegal war in Ukraine – the Breton-era European Commission has built its central legacy in the digital field around moves to slow down, regulate and tax successful American Internet companies. To be sure, the Internet does need smarter and better regulation and those companies probably could stand to pay more in taxes. But the European plans have had something else in mind. The measures proposed – and the sender-pays levy is no exception – have been overtly punitive – looking mostly to harm or slow down successful American companies and doing very little to put in place a thriving European ecosystem or build up successful European companies instead. With the European Innovation Council being a notable exception, the single market remains a little noticed, seldom used tool in this European Commission’s arsenal. The result is, broadly speaking, a weaker European digital sector – one with less competition and fewer tools for local champions to build on and advance.

The telcos have complained for years that the European Commission had dealt them a lousy hand. They say that the price-cap on roaming charges curtails their income in a place where revenue was once easy to generate. And they bemoan that European competition policy prevents them from consolidating across European borders. Europe has no AT&T Inc. or fully grown baby bells even though the logic of the internal market would have dictated the emergence of consolidated European champions years ago – companies with the firepower to address European investment needs as readily as the American companies do now.

The European Commission has held the line firmly on those two points. It has refused to give in on roaming charges. And it won’t change competition policy to allow cross-border consolidation. But the “sending-party pays” proposal offers a useful way out. It’s a handy sop to the telco companies at the end of an era when some bosses seem to feel that Commissioner Breton hasn’t done enough for them despite five years on the job. And the tax payer doesn’t even have to pay. The “very large platforms” will do it. But this is not true. If the plan goes through, the burden will fall directly on consumers in the form of fewer choices, less innovation, lower quality of services and ultimately higher prices for goods they consume liberally at competitive prices today.

Konstantinos Komaitis is senior researcher and non-resident fellow at the Lisbon Council, a Brussels-based think tank. He is the author of The Current State of Domain Name Regulation: Domain Names as Second Class Citizens in a Mark-Dominated World, a 2010 book. He is co-host of “Internet of Humans,” a podcast. Follow him on Twitter at @KKomaitis.

Paul Hofheinz is president and co-founder of the Lisbon Council. Follow him on Twitter at @PaulHofheinz.